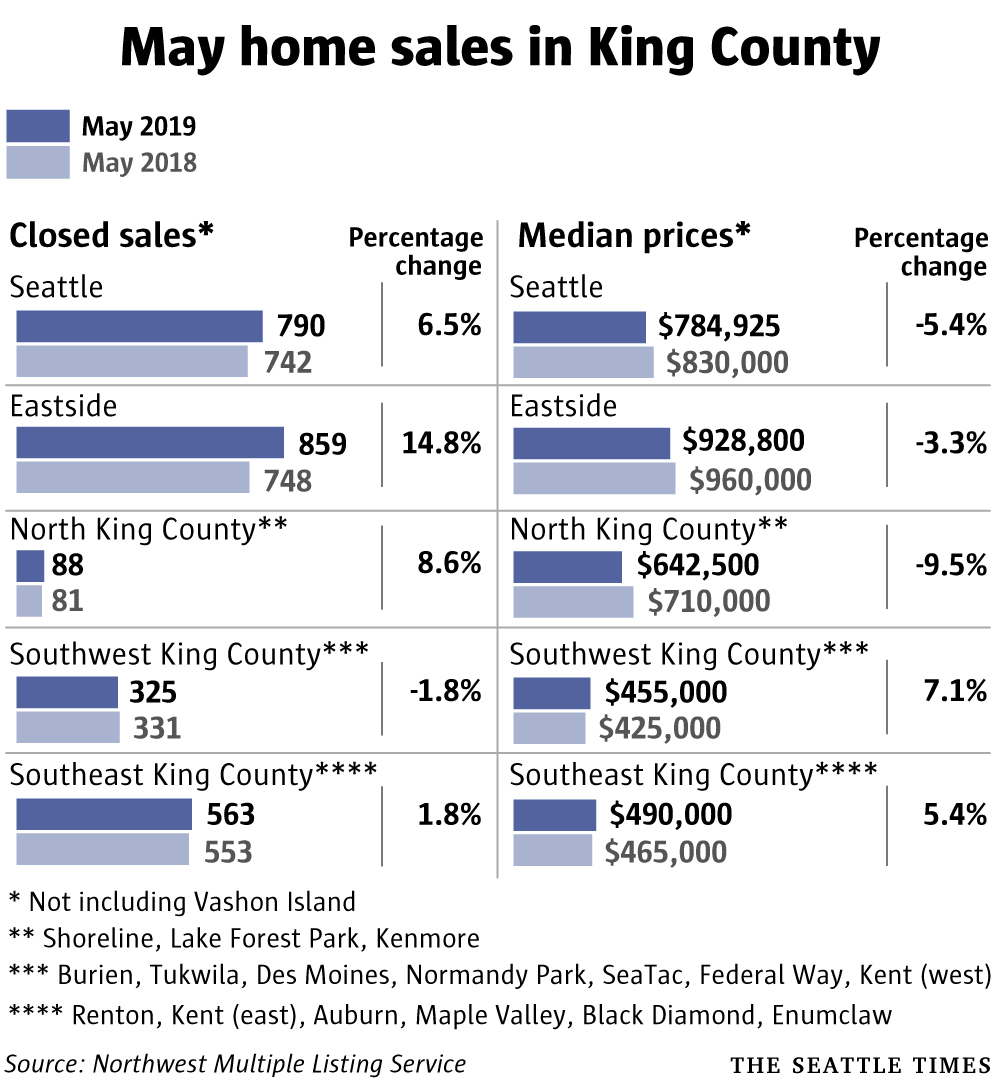

The Seattle-area housing market has clearly split into two: Buyers looking for higher-end homes in pricier cities like Seattle and Bellevue aren’t paying any more than they did a year ago. Meanwhile, those shopping around for something resembling a deal, perhaps in Tacoma or Everett, are still confronted with the same old hot market from years past.

The national Case-Shiller home price index, released Tuesday, showed Greater Seattle had one of the coolest housing markets in all the land when looking at the full metro area.

Prices regionwide in February grew 2.8% from a year ago, below the national average of 4%. Among the 20 regions covered in the report, only four — San Diego, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago — had smaller price increases.

But the regionwide average — which spans King, Snohomish and Pierce counties — covers up vast differences when you zoom in closer.

The report divides the region into three even price tiers, roughly those homes selling for above $600,000, those below $385,000 and those in between.

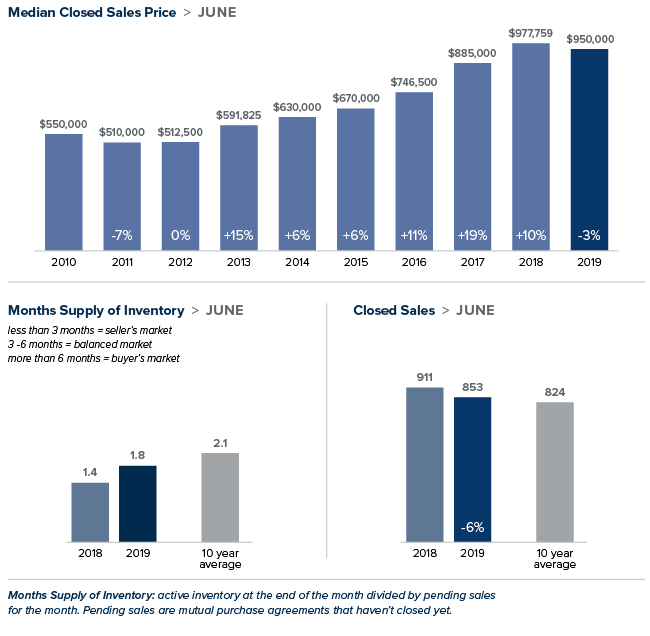

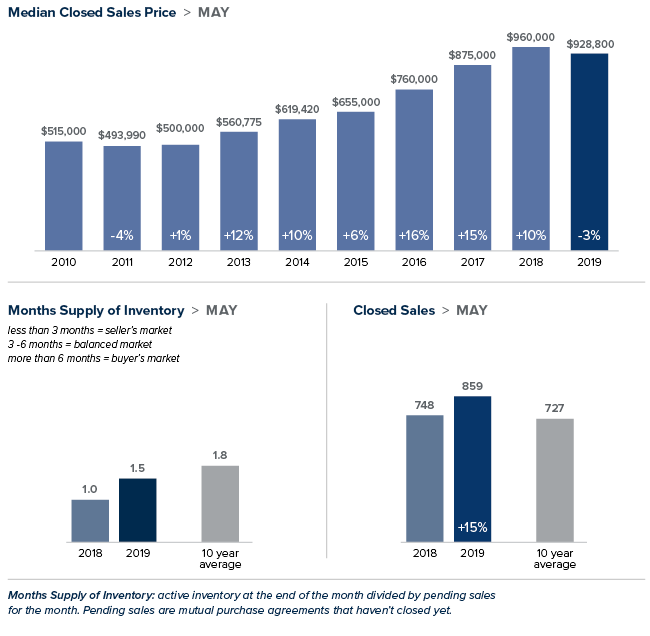

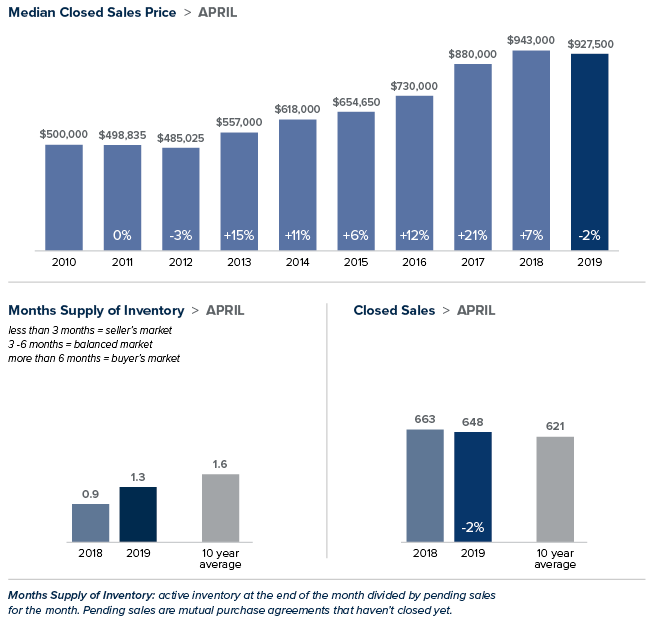

Home values on the priciest level, which would include most homes Seattle and the Eastside, actually dropped a smidgen on a year-over-year basis. Prices even dipped slightly on a month-over-month basis, defying the normal seasonal gains.

How unusual is that? The last time any segment of the market saw prices drop on an annual basis was eight years ago, when home values bottomed out following the recession. Flash back to this time last year and the priciest homes were surging 12% in value.

But look at the cheapest group of homes, typically found in the outlying parts of the metro area, and it’s like traveling to an entirely different area: These saw prices grow about 8% from a year prior, including a jump of 1.5% just in the last month.

For perspective, only one region, Las Vegas, had a bigger annual price bump when looking at regions as a whole.

Homes in the middle-price bracket, which you might find in Lynnwood or Renton, saw prices grow 3.5%, slightly below the national average.

In Dan “Dan-O” Olague’s Puyallup real estate office, “it is back to a hot market.”

“Anything under $300,000 has not lasted more than a week,” said Olague, of John L. Scott Real Estate. That’s about as quickly as a home can conceivably sell.

He noted a 1,300-square-foot house in Spanaway he recently listed for $269,000 – and quickly got 14 offers, with some going over $300,000.

As has been the case, more buyers are coming down from King County, particularly for homes in Tacoma along the Sounder train line, where a house that can be had for $400,000 might cost $700,000 or more in Seattle.

“They can buy more house down here than they can in King County,” Olague said.

Up north, Jerry Melchisedeck, director of operations for RE/MAX Elite’s Snohomish County bureau, said “there’s a marked difference between the homes in the $300 and $400,000s and how quickly they’re selling vs. higher price points.”

“I’d expect that (lower) price point to continue be to very competitive,” he added.

John Manning, who owns a RE/MAX branch in Ballard but has listings in Snohomish County, said he’s seen an influx of empty-nesters moving to more affordable, smaller homes up north. And with Amazon picking up its hiring in Bellevue, there has been more activity from its employees looking in Kenmore and north across the county line, he said.

Why the divergence between the higher- and lower-cost markets? There are fewer people out there snatching up higher-end homes, making competition less hectic than it used to be.

The number of homes for sale across the Seattle area has grown faster in the last year than anywhere except San Jose, according to Redfin.

The surge is almost entirely attributable to homes sitting on the market unsold for longer: Home sales here are dropping at among the fastest rates in the country, as well. Most of those stale homes not getting offers are on the higher-end side of things.

To Read full article on SeattleTimes.com, click here.

April 30, 2019 at 6:53 am Updated May 1, 2019 at 12:10 pm

Prices of single-family homes across the Seattle area aren’t soaring the way they used to. (Greg Gilbert / The Seattle Times)

By

Mike Rosenberg

Seattle Times real estate reporter

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link